If the suit didn’t give it away, you could tell from his manner that he’d done well for himself. Andy had done a bit of everything. Five years’ work in the WA mines had set him up to make some smart investments. Andy was a ‘self-made’ man, with a dozen businesses behind him and two failed marriages along the way. These days he worked as a consultant to the coal industry (‘Carbon budget, my ass’, he said. ‘The stuff’s in the ground, it’s coming out’). He liked how the Asians partied with a bottle of whiskey on the table. We bonded over shots at the bar, but the more we talked, the more the years yawned like a chasm between us.

He laughed when I told him that I was a philosopher. ‘So am I’, he said. ‘I’m a professional cynic’.

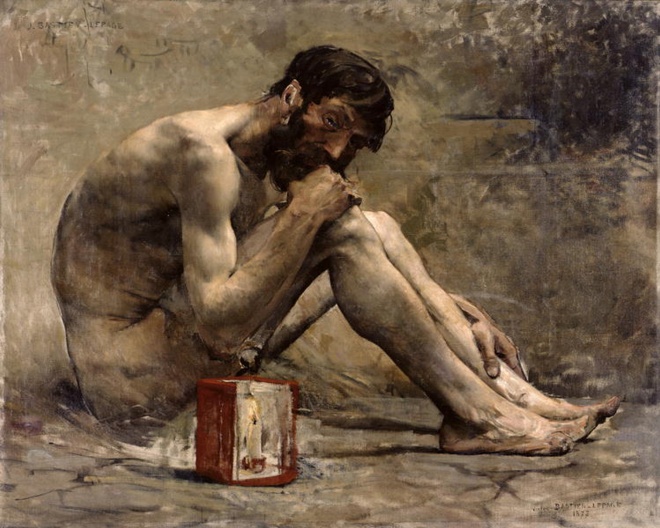

Cynicism used to be a dirty word. When Andy and I were kids, we wouldn’t have thought of affirming it. To be cynical means to be distrusting of people’s motives and dismissive of their good intentions. Only a fool would want to try to change the world. Cynics are convinced that everyone operates out of self-interest. Given this state of affairs, the only smart response is to take care of number one. In business life, cynics are distinguished by a ‘me first’ mentality. They don’t care much where they make their money. If the money’s easy, it’s good. Often, you’ll find them working for pariah industries like coal and tobacco. They are working for a broken system, and they know its going nowhere, but they’re riding the gravy train to the end.

I am troubled by the easy affirmation of cynicism in contemporary life. To my mind, the fact that successful people like Andy know that things are getting worse; also that aspects of their existence are helping things to get worse; yet think the matter is out of their hands, that it is beyond their power to do or change anything, so they may as well be cynical – this amazes and upsets me. ‘Pretty stupid not to be cynical, these days’, Andy laughed when I pressed him on the issue. ‘Take it from me, mate, it’s a pack of dogs out there’. He squared his shoulders and knocked my glass with his drink. ‘Chi-ching’. Same old Andy. Yet something had changed – I could see it in his eyes. It was a flicker of fear. Our conversation was taking him places that he rarely went. Difficult places. His cynical philosophy gave him license to live the way he wanted. But did it allow for journeys of the mind? Did the old school battler have the courage to think? [Read more…]