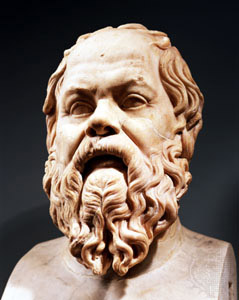

Life Changing is a hands-on guide to harnessing the power of change. Using philosophical examples, it shows you how to cultivate the resilience, agility and vision to embrace change and make it an adventure.

The book includes practical exercises that enable you to apply the ideas in familiar contexts. By doing the exercises, you learn how to think philosophically about change and unleash its life-changing possibilities.

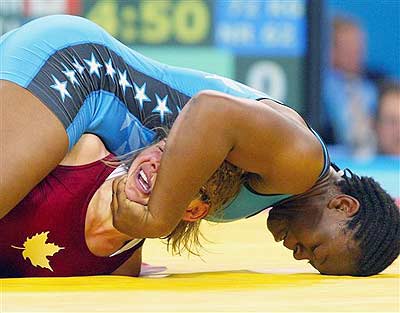

Be creative with change. Don’t just ride it out — use it.

Life Changing: A Philosophical Guide is available on Amazon, Kobo, and iTunes.

Check out the introduction to Life Changing on the P2P Foundation wiki.

Life Changing marks the end of a personal journey. For the past fifteen years, I have been studying, teaching, and applying transformative philosophy in my own life, first as a doctoral student at the University of Sydney, then as a lecturer at the Universities of Sydney and New South Wales, and recently in my Philosophy for Change course, which I’ve run at the Centre for Continuing Education, University of Sydney. My guiding intuition has been that it is possible to distil from philosophical ideas a kernel of practical wisdom, which can be communicated through simple exercises that students can apply to their lives.

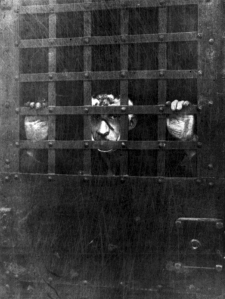

This intuition is core to Life Changing. The book is structured about five practical exercises. Each incorporates a life-changing insight. The exercises show you how to muster the courage to change; how to control yourself like a Stoic philosopher; how to cultivate your Nietzschean will to power; and how to use Spinoza’s philosophy to supercharge your social life. They show you how to take adventure from the heart of crisis and fulfilment from the struggle with adversity. [Read more…]